When the English king Edward the Confessor died, there were several contenders for the throne.

Harold Godwinson was in England at the time and was proclaimed king by the Witan, a council of nobles and priests.

The Norman William the Bastard also laid claim and prepared an invasion that would later lead to the decisive Battle of Hastings.

Harold prepared to block his landing, but had to wait for months because William was held up by bad weather.

In the meantime the third contender, Harald, suddenly landed in Northumbria and opened the fighting.

Harald's path had been prepared by earl Tostig, brother of Harold, who had fallen out with each other.

Tostig had spent the summer mounting a number of attacks on north England.

In September he was joined by Harald, who brought a fleet of some 200 longships, 100 supply ships and 8,000 warriors.

Together they engaged Edwin, the earl of Mercia, in the Battle of Fulford and defeated him with 2/3 of their army,

mostly by the advantage of the experience of the leaders and their men.

Deprived of its defenders, the city of York surrendered to them and the Vikings set down to rest.

It was late in the campaigning season and Harold, waiting in the south, had already disbanded part of his army.

When he heard of the events, he immediately set off towards this new threat with the core of his army, his housecarls.

The Saxons made a forced march, covering 300 kilometers in less than a week.

Along the road Harold picked up reinforcements where he could find them, increasing his strength from 3,000 to somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000.

The sudden arrival of the Saxons caught the Norse, who were busy receiving hostages and booty from York, completely by surprise.

Their army was already smaller than at Fulford and a third of it was with their ships at Riccall, so at first only only a few thousand fought in the battle.

The attackers were weary from their march, but Harold, intent on exploiting his surprise advantage, immediately ordered an attack.

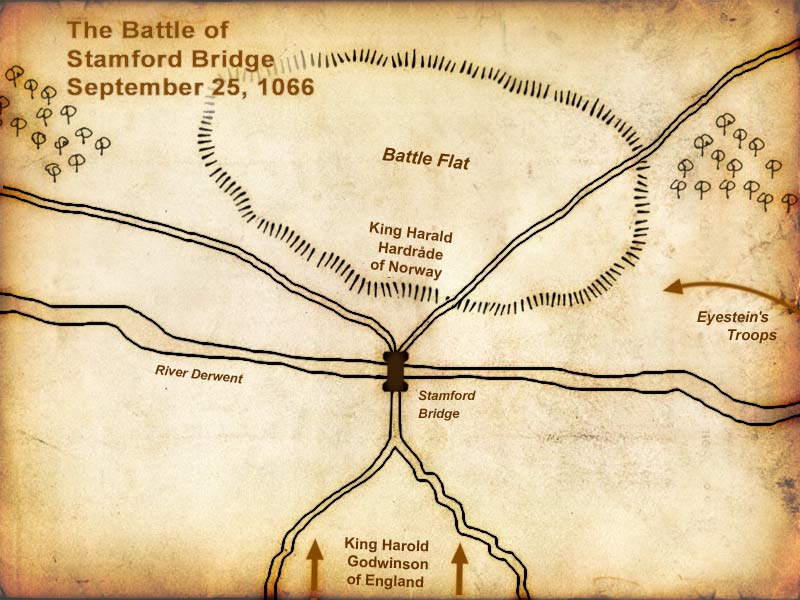

The Norsemen on the western side of Stamford Bridge were quickly cut down, however according to the Anglo-Saxon chronicle the advance was halted on the bridge.

A giant Viking, who wielded a large axe, alone held off his opponents on the narrow passage,

until some men crept under the bridge and killed him by thrusting their spears upwards through cracks.

This obstacle cleared, the Saxons attacked the main Norse army, which had hastily drawn up a shield wall on a low hill behind the bridge.

Most had not gotten enough time to don their armor and so fought with weapons and shields alone, which made them vulnerable.

Harold then briefly negotiated, though when it became clear to the Norsemen that Tostig might be pardoned but Harald only buried, they chose to fight.

The battle raged fiercely for hours.

The attackers managed to slowly outflank them and cut holes in the shield wall.

After both Harald and Tostig were slain, the Norse line disintegrated.

Later other parts of the Viking army under Eystein Orre arrived.

These were fully armed, but nearly exhausted from an 12 kilometer run in armor on a hot day.

Nonetheless they were desperate to regain the upper hand.

They briefly checked the Saxons, but soon were pushed back also, then broken and routed.

Harold's tactic of attacking immediately had worked very well.

Thousands of Norsemen, almost the entire army, lay dead on the battlefield.

The remainder had to promise they would leave England forever and retreated to the Orkneys, then back to Norway.

It was the last time that a Scandinavian army ever invaded England.

But in the meanwhile William had landed in Sussex, so Harold had to march south again to fight a second battle.

He had won the first but would perish in the second.

War Matrix - Battle of Stamford Bridge

Viking Age 800 CE - 1066 CE, Battles and sieges